- Part Zero: An Introduction

- Part One: A History

- Part Two: Card Advantage, Tempo, and the Philosophy of Fire – Section One

In previous sections, we discussed why the study of Magic Theory is vitally important to the development of any Magic player. We also explored the history of Magic Theory itself and the people who have helped to shape it, all while taking a few cursory glances at the concepts involved. We will now begin an in-depth, rigorous examination of each of the elements of Magic Theory in order that we may gain the understanding necessary to move forward toward our own speculations about what occurs behind the physical reality of an individual game of Magic: the Gathering – a metaphysical understanding of the game’s structure, if you will. We start in this part of the article series with the three fundamental building blocks of Magic Theory: Card Advantage, Tempo, and the Philosophy of Fire. We examine the first of these topics, Card Advantage, in this section.

Section I – Card Advantage

Drawing extra cards is effective in and of itself. –Brian Weissman

Card Advantage was the very first building block of Magic Theory discovered, and since its inception, has been the central topic in almost any theoretical discussion about the game. To wit, it is usually the first Magic Theory buzzword a player learns as he begins to develop competitively. In fact, most competitive players seem to have a basic working knowledge of the concept simply from their experience playing in a tournament setting, even without a formal briefing on definitions; however, there tends to be some confusion about certain cases which don’t fit perfectly within the layman’s understanding of the topic. Is Midnight Haunting Card Advantage? Well, sometimes. Or, why is it that Brainstorm is compared to Ancestral Recall, perhaps the most cost efficient Card Advantage spell of all time, when Ponder is not, despite the fact that their effects are so similar on the surface?

These kinds of questions allude to a very intricate framework of theory upon which Card Advantage sits. They are part of the 80% of the proverbial iceberg which lies below the surface of the water. Since we’re in the business of understanding icebergs, if I may be permitted to extend the metaphor, we’d like to be able to study that 80%, but perhaps it’s best that we begin with the 20% we can see above the surface, as it’s more readily accessible. So what, then, is Card Advantage on the surface?

If a sequence of plays (or decisions) ends with a player up one or more cards, that player has gained card advantage. –Steve Sadin

Trying to discover a basic definition of Card Advantage in the writings of the great Magic theorists is surprisingly difficult. Most of them begin with the hedge, “Card Advantage has been discussed previously ad nauseam, so I won’t bother to redefine it here,” and then go on to cover some more advanced concept or topic. Unfortunately, this lack of conciseness on the subject exists for good reason; and that reason is that a concise summarization of everything that the term Card Advantage entails is nigh impossible. But that doesn’t mean we can’t try.`

Patrick Chapin brought up an important point in his article, The Theory of Everything, where he suggests that Card Advantage is really only one side of a spectrum of effects having to do with the number of cards a player has available. He calls this spectrum Card Economy, and we will adopt this terminology. It follows that a general definition of Card Economy will be more useful to us, as we can merely extrapolate from that concept down to the more specific notion of Card Advantage. So what is Card Economy?

| Card Economy is a quantifiable evaluation of how many cards a player has available relative to the number of cards an opponent has available. |

Let’s examine what this definition actually means:

- Being quantifiable implies that there is an objective means of determining exactly how many cards a player and his opponents have available.

- A card being available means that it either a) could be cast by its owner all things being equal, or b) can execute some relevant function from whatever game zone it occupies.

- Being a relative evaluation means that Card Economy exists as a zero sum ratio between card availability of two or more players. In other words, what is Card Advantage for a player must be Card Disadvantage for at least one of his opponents.

Perhaps we should look at a few baseline examples:

Player A controls a Grizzly Bears, and player B Shocks it. This is neutral Card Economy, as player A and player B have cast one card each and neither of those cards are now available to said players.

Player A controls a Centaur Courser, and player B Shocks it. This is negative Card Economy for player B, or Card Disadvantage, because each player has cast one card, but player A’s card is still available, while player B’s is not.

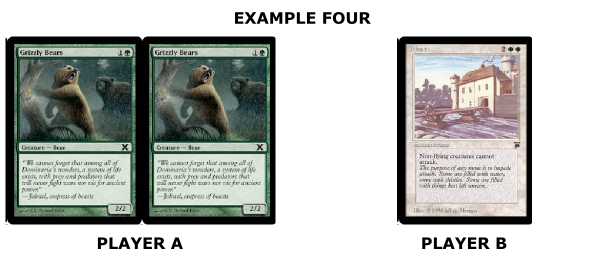

Player A controls two Grizzly Bears and player B attacks with a Centaur Courser. Player A blocks the Courser with both of his Grizzly Bears. Before damage, player B shocks one of player A’s Bears. This is positive Card Economy for player B, or Card Advantage, because each player has cast two cards, but after combat player A still has one available, (his Courser) while player B has none.

These are three of the most basic examples one can possibly conceive to graphically illustrate the differences between negative, neutral, and positive Card Economy. While real world games of Magic are going to involve much more complex situations which are often much more difficult to conceptualize in an axiomatic way, every such scenario is going to be representable, in some way, by these examples. Therefore, if we still wish to have a working definition of Card Advantage, perhaps this is what it would be:

| Card Advantage, that is positive Card Economy, is any state in which a player, through casting or utilizing a function of the cards he has available, ends up with more available cards relative to an opponent than before he cast or utilized a function of the cards involved. |

Card advantage at its most basic simply means having more cards than your opponent over the course of a game. –Ted Knutson

But here’s where things become a touch complicated. Example three above is a case of what is often referred to as Real Card Advantage; so we will say that all of the examples above deal with Real Card Economy. However, there exists another recognized form of Card Advantage referred to as Virtual Card Advantage; so we will have to discuss the notion of Virtual Card Economy. First, what is Real Card Economy?

| Real Card Economy is Card Economy in which all of the cards involved interact directly. |

Real Card Advantage is often called Cardboard Advantage, because the cards which are interacting are the actual cardboard cards. This doesn’t make much sense outside of a context, so a better way to describe the dichotomy between Real and Virtual Card Economy is to figure out what kinds of card interactions do not occur directly. Let’s look at a few more examples:

Player A controls two Grizzly Bears and player B controls a Moat. In terms of Real Card Economy, there is neutrality, because all of the cards are potentially available to their controllers. However, player B has a Virtual Card Advantage because player A’s Grizzly Bears no longer have any functionality. They may as well not exist. In other words, player B has spent one card to blank two of Player A’s cards. But the interaction goes a little deeper. If player A has no way to remove player B’s Moat, then every single non-flying creature in player A’s deck which doesn’t have an auxiliary functionality outside of attacking is now a dead card. If player A draws one of those cards, then player B’s Moat has produced additional Virtual Card Advantage, in that player A has automatically lost the availability of the card even upon drawing it.

Player A controls a Garruk Relentless on three loyalty and two Wolf creature tokens produced by the Planeswalker, while player B controls two Centaur Coursers. Player B attacks Garruk with both Coursers and player A decides to block one of them with both Wolf tokens. Garruk, one of the Wolves, and one of the Coursers all die from combat damage. From a strict Real Card Economy perspective, there is once again neutrality, because both players lost a single cardboard card during combat. But in reality, player A has produced Virtual Card Advantage, because his opponent has lost a card, but he hasn’t lost any. Wait, what? The Garruk died, did it not? Yes, the cardboard card Garruk was put into the graveyard, but one of his Wolves survived combat. One of Garruk’s functions is to produce Wolf tokens, and so long as at least one of those tokens is available to its controller, Garruk still plays a role in the calculation of Virtual Card Economy. (It’s worth noting if player B has his remaining Centaur Courser abstain from combat, it can do a pretty good Moat impression, keeping player A’s remaining Wolf token from attacking, thereby regaining neutral Card Economy. That is, until player A uses a Lightning Bolt to destroy player B’s remaining Courser, in which case player A would once again gain Virtual Card Advantage.)

As a reverse example, Player A controls a Bitterblossom and three Faerie Rogue creature tokens produced by the enchantment, while player B controls four Squadron Hawks, the first of which searched for the other three when it entered the battlefield. Player B attacks with all four of his Hawks, and player A blocks three of them with his Faerie tokens. It would appear on the surface that there is neutrality from both Real and Virtual Card Economy perspectives; player A still has his Bitterblossom and player B still has one remaining Hawk, which is the only one he needed to draw naturally. (As far as Card Economy is concerned, the other three Hawks were as “free” as player A’s three Faerie tokens.) While this is technically true for Real Card Economy, once again the surface appearance is not the reality. Player A has put himself into a Virtual Card Disadvantage because his Bitterblossom is not immediately exerting any functionality. In other words, Bitterblossom is only an agent of Virtual Card Economy when there is at least one of its tokens on the battlefield, or what I am going to refer to as being immediately available. However, player A will regain neutral Card Economy during his next upkeep, when his Bitterblossom produces another Faerie token.

Example six above illustrates an important point which has been yet undefined by Magic theorists. Zvi scratched the surface of this concept in his article, Advantage – VCA and Tempo, under the section heading, Virtual Card Advantage: Uncastable Cards, where he discusses whether or not a card which is in a player’s hand but which he does not currently have the resources to cast or otherwise utilize, should be considered a blank. Unfortunately, he never draws a concrete conclusion, and a precise answer to this conundrum is likewise never reached satisfactorily in any other writings. So it is left to us to develop a conceptual framework.

| A card is potentially available when it could, at some point in the game, given the functions of the cards currently exerting an effect within the game and an appropriate development of resources, be cast or otherwise utilized. A card is immediately available when it could be cast or otherwise utilized at the present moment in the game, or it is currently and directly exerting a function within the present state of the game. |

The potential availability of a card causes it to be counted positively toward a calculation of Real Card Economy, while the immediate availability of a card causes it to be counted positively toward a calculation of Virtual Card Economy. As in example six above, the Bitterblossom sitting in play across from a lone Squadron Hawk counts as a potentially available card because it has been cast and will in the near future exert its primary function of producing a Faerie token, and is therefore at neutral Real Card Economy with the Squadron Hawk; however, it is not immediately available because it is not currently nor directly exerting a function within the present state of the game, and is therefore at negative Virtual Card Economy with the Squadron Hawk.

From the examples above and this clarification of terminology, we can now attempt to construct definitions for Real and Virtual Card Advantage:

| Real Card Advantage is Card Advantage in which only the potential availability of a card is considered when calculating the number of cards available to a player relative to an opponent. |

| Virtual Card Advantage is Card Advantage in which only the immediate availability of a card is considered when calculating the number of cards a player has available relative to an opponent |

All of this might be a little confusing, so let’s talk about a few things which are or aren’t Real or Virtual Card Advantage:

- Example Seven: Divination is Real Card Advantage because the player who casts it spends one card to draw two potentially available cards. However it may or may not be Virtual Card Advantage, depending on whether or not the cards he draws are immediately available. If he draws two spells which he could currently cast, then it is Virtual Card Advantage, but if he draws a spell which he cannot currently cast and a land he cannot currently play because he already played a land this turn, then it was Virtual Card Disadvantage, because he spent one immediately available card to draw two cards which are not immediately available.

- Example Eight: If a player casts a Wrath of God while he controls a Moat and none of his own creatures, and destroys two of his opponent’s Tarmogoyfs and a Baneslayer Angel, he has produced a Real Card Advantage of three cards to one, but has neutral Virtual Card Economy because he spent one immediately available card to destroy one of his opponent’s immediately available cards and two cards which were not immediately available. Incidentally, unless the player’s opponent has a non-flying creature in his hand, the player actually finds himself at a Virtual Card Disadvantage after the fact, because his Moat is no longer immediately available, as it has no current function.

- Example Nine: Brainstorm is neutral Real Card Economy because the player who casts it ends up with the same number of potentially available cards in his hand as he began with, just the same as if he had cast a Ponder. However, Brainstorm allows a player to trade cards in his hand which are not immediately available for cards which could potentially be immediately available now or in the immediate future, especially if he has an effect that allows him to shuffle his library after it resolves, such as a Polluted Delta. This is why Brainstorm is considered one of the best cards in Magic, because it has the ability to convert one mana, one immediately available card, and two cards which may not be immediately available into three potentially available cards. This means that it can produce anywhere between a Virtual Card Disadvantage of one card in a rare worst case scenario, to a Virtual Card Advantage of three cards to one. Compare this to Ponder, which is never capable of producing more than a neutral Card Economy. (That isn’t to say Ponder is a bad card, because it certainly isn’t; but it’s strength lies only indirectly in the realm of Card Economy. The card is generally used as a means of increasing the probability of drawing immediately available cards in the future.)

It is crucially important that Card Economy be examined within a specific context within a specific game of Magic, as we have seen in all of the above examples. Attempting to keep a running tally of the total net Virtual Card Advantage between two players throughout an entire game of Magic is the ultimate endeavor in futility without an external framework to convert the numbers into relevant information, which we will talk about later in this article series. As we saw in examples six and eight above, with the lone Bitterblossom or Moat, what is Virtual Card Disadvantage in one game state can become a Virtual Card Advantage later, as an opponent struggles to find answers to the multiplying Faerie tokens or draws non-flying creatures, respectively. Likewise, producing exponentially more Real Card Advantage than an opponent through draw spells means nothing if a player can’t convert those cards into a Virtual Card Advantage, or in other words, if none of said cards are or can become immediately available.

Card advantage matters when a lack of useful cards starts to punish one player, or the threat of a future lack of cards punishes that player. –Zvi Mowshowitz

We’ve spent an awful lot of time discussing what Card Advantage is, but we haven’t talked much about why it is important within the context of a game of Magic. While the full extent of this concept’s relevance requires the aid of both Tempo and the Philosophy of Fire, and is therefore the primary subject of so-called Unified Theories of Magic which we will be examining later, we can nonetheless gain a basic understanding of Card Advantage’s importance as an autonomous force in Magic theory.

As Zvi pointed out, Card Advantage’s primary relevance exists in an evaluation of how useful each card a player has available is to that player’s progression toward winning a game. This sentiment clearly highlights Zvi’s Rule of Reflection which is postulated in his article, Advantage: The Grand Unified Theory, where he states: “Everything in Magic has value equal to the amount it increases your chance to win the game.” If winning a game is important, then clearly having access to cards which will win you the game, all things being equal, should be a preeminent concern for any player.

If viewed in a certain light, ending a game of Magic victoriously is about overpowering an opponent with Virtual Card Advantage, in that one must reduce to zero the number of immediately available cards an opponent has access to. This is essentially synonymous with what Patrick Chapin has to say about the goal of a player in his Option Theory: “The object of a game of Magic is to take away [the option to continue playing the game] from your opponent.” Two effective ways a player has of doing this within the context of Card Economy is to a) increase his total Real Card Advantage in order to have access to more potentially available cards, and/or b) cast and utilize cards which produce a net Virtual Card Advantage within isolated game contexts.

Fundamentally, the theory of Card Advantage teaches us that drawing cards and having access to efficient cards can dramatically increase our ability to win a game of Magic: the Gathering.

Very anxious for more in this series.